The Surviving Eggs of the Great Auk

Great Auk eggs hold immense scientific and cultural value. Physically, they are striking objects; large, boldly patterned shells that once nurtured the last generation of an extinct bird. Historically, each surviving egg carries a rich provenance, often involving famous naturalists and illustrious collectors. These eggs have been treasured, traded, copied, and even occasionally lost through accidents of history. In this article, we capture a snapshot of our current knowledge of these poignant relics. We will discuss their appearance, history and their role in contemporary culture and science. Our story is illustrated using egg replicas and bird renders from the author along with an exhaustive catalogue of the remaining 75 eggs. The preservation and study of the Great Auk’s eggs ensure that the lessons of its extinction are not forgotten by future generations.

Introduction

The Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis) was a flightless seabird of the North Atlantic that went extinct in the mid-19th century. It was driven to extinction in large part due to overhunting for its feathers, meat, and eggs. Its eggs became coveted relics after the species’ demise. Today, only 75 authentic Great Auk eggs are known to survive worldwide. These reside mostly in museum collections across Europe and North America.

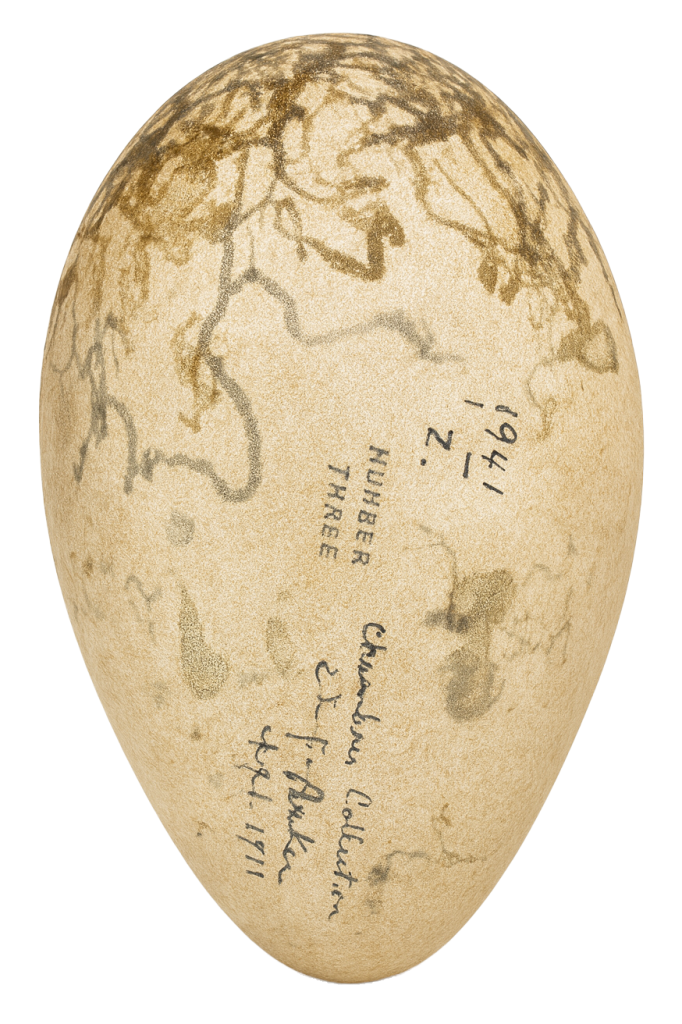

Each egg is unique in size and pattern. All share a general appearance of being about 12–13 cm long and 7–8 cm at the widest point, with a pyriform (pear-shaped) or elongated ovoid form. They are a cream to buff white background boldly marked by black or brown streaks, blotches and scrawls which are often densest at the larger end. The striking “marbled” or “scribbled” pattern of Great Auk eggs made them especially prized by collectors.

Naturalists have attempted to catalog the remaining eggs since the bird’s extinction. In 1885, Symington Grieve could locate 68 eggs worldwide. By 1911, Thomas Parkin reported 73 eggs (with a 74th discovered in 1918). A comprehensive census by the Tomkinson brothers in 1966 identified 75 eggs, incorporating new finds and known specimens. A few eggs have been lost or destroyed over time. For example, one in the Dresden museum was likely lost during World War II, and another destroyed by fire in 1872.

Many eggs traded hands multiple times in the 19th and early 20th centuries, moving from one collector or dealer to another as their value steadily rose. By the mid-20th century, however, the majority had found permanent homes in museums, bringing more stability to their ownership. For example, in 1892 only 29 eggs were in public museums with 42 in private collections, but by 1965 at least 54 were held by museums and only 18 remained in private hands. One notable collector, Captain Vivian Hewitt of Wales, amassed 13 Great Auk eggs, the largest private holding ever, by the mid-20th century. After Hewitt’s death in 1965, five of his eggs were sold via a London dealer and the remaining eight were eventually acquired by another collector, Dr. J. “Jack” Gibson, in 1992. Most of those have since been dispersed again, illustrating how even in recent decades a few eggs have moved from private collections into public institutions or other hands. One Great Auk egg was sold at auction in 2023 for over $125,000. Nearly all are now housed in public museums, which ensures their preservation and accessibility for study. Only a handful remain in private collections today.

The accompanying image shows two Great Auk eggs from a museum collection, illustrating their size, shape, and typical markings. These eggs have a creamy base color with irregular dark streaking (one egg even bears a handwritten label, “Pingouin,” the French word for auk, on its shell).

Two Great Auk eggs in the collections of the French National Museum of Natural History (MNHN), showing the elongate shape and dark streaked markings characteristic of the species’ eggs.

Catalog of Surviving Great Auk Eggs

Here is a comprehensive catalogue of the 75 known surviving Great Auk eggs, detailing their physical characteristics and documented histories. Each entry includes an identifying egg number, the current location, approximate dimensions, a brief description of shell coloration/pattern, a summary of known collection history (from earliest known origin through notable owners), and the egg’s current status (extant in a collection, or missing if its whereabouts are unknown). The data are synthesized from historical catalogs of Grieve 1885; Parkin 1911; Bidwell 1892 MS; Tomkinson & Tomkinson 1966. The latter is used as the definitive egg numbering system.

Patterns and Variation

The markings on Great Auk eggs are famously variable, ranging from dense blackish-brown squiggles covering much of the shell to almost unmarked examples. Despite this individual variation, the pyriform (pear) shape and patterning is unmistakable. The most profusely marked egg, the Earl of Derby’s egg in Liverpool, has been likened to a Jackson Pollock painting for its wild tangle of looping streaks. In contrast, Yarrell’s egg, has only a few faint marks and streaks at the large end. Most Great Auk eggs show an intermediate degree of bold, erratic lines concentrated toward the thicker end. Notably, certain eggs have unique hues. For example, the Harvard egg #54 is described as having beautiful pale greenish-grey markings, unlike the usual deep brown or black. Shell texture vary from very rough to smooth but most have a definite matt surface. The average dimensions are 12.9 cm long by 7.8 cm wide. An especially small egg (#50, “St. Pierre-Miquelon”) is only ~11 cm long. At the larger end, eggs up to 13.3 cm are recorded. Overall, however, Great Auk eggs are fairly uniform in size compared to many birds, reflecting the species’ one-egg clutch strategy and similar body size across the population.

Identification and Labels

Many eggs carry inscriptions or old catalog numbers physically written on their shells, which have become key clues to their provenance. For instance, egg No. 58 in Aberdeen bears the handwritten word “Pingouin” (French for penguin). This label is believed to have been inscribed by M. Dufresne, curator of the King’s Cabinet in Paris in the early 1800s, indicating the egg was once in the French royal collection. Likewise, egg No. 41 still shows “330A No. 1” on its shell, a code attributed to Lord Garvagh’s private catalog in the mid-19th century. Egg No. 7 has the numeral “61” written on it, and egg No. 2 has “130” (or possibly “139”) on its small end. These likely correspond to 19th-century dealer or museum numbering systems. Dr. John Leach of the British Museum numbered some eggs, and “130” may match an entry in his records. Another striking example is egg No. 50, marked “St. Pierre-Miquelon”, suggesting it was collected from that North American locality. Indeed, the French islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon near Newfoundland were frequented by auk hunters, so this egg probably traveled to France from there in the early 1800s. These inscriptions, often faded, are carefully preserved and documented as they directly tie the specimen to historical collections and sometimes even to specific voyages or collectors. They also illustrate the practice of the era: collectors often wrote on eggs in ink to record their acquisition or origin. Something modern curators would avoid, but which now provides invaluable pedigree information.

Provenance and Collecting History

The journey of each egg from an auk rookery to a museum cabinet is often complex, involving multiple owners and sales. A common thread is the frenzy of Victorian-era collecting. When the Great Auk went extinct in 1844, prices for its eggs skyrocketed. By the 1850s–1900s they fetched sums equivalent to several years’ wages for a skilled worker. Many eggs passed through the hands of prominent 19th-century dealers such as John Leadbeater, James Gardner, Edwin Stevens (of Stevens’s Auction Rooms), and the Paris dealers Lefèvre, Parzudaki, and Depierre. Several aristocratic collectors amassed multiple eggs. Lord Lilford (Thomas Littleton Powys) had five eggs at one point, Baron d’Hamonville in France owned four, Robert Champley in Scarborough had nine, and Capt. Vivian Hewitt in Wales eventually assembled the largest private hoard of all: 11 eggs. The dispersal of these collections significantly shuffled the whereabouts of eggs. For example, when Champley died, his nine eggs were mostly acquired by others. One went to Scarborough (#15), a few ended up with Hewitt. Hewitt’s own extraordinary collection, built in the 1930s–40s from auctions and trades, including many of Rowley’s and d’Hamonville’s eggs, was itself broken up after his death in 1965. Recent research has traced Hewitt’s eggs. Eight were acquired around 2002 by Jack Gibson, who offered them, along with Hewitt’s library, to the National Museum of Scotland. Ultimately, several Hewitt eggs are now in Edinburgh while others, like Yarrell’s Egg, were resold to private collectors or specialists. Natural history author Errol Fuller owned Yarrell’s egg for a time in the 2000s before it was auctioned.

The Rowley collection was another pivotal point in many eggs’ provenance. John Hancock’s Museum in Newcastle and the auction rooms of London saw heated bidding when Rowley’s estate was liquidated in November 1934. In that single sale, six Great Auk eggs were auctioned, the greatest number ever sold in one day. Hewitt acquired four of them, two others went to G.N. Carter and Sir Bernard Eckstein. This underscores how a few key transactions redistributed eggs from older collections into modern ones. Notably, all six Rowley eggs are accounted for, showing up under Hewitt’s ownership and thence to subsequent repositories.

Another interesting episode is the discovery of ten Great Auk eggs at the Royal College of Surgeons (RCS) in London in 1861. These eggs had languished unidentified in a museum storeroom, labeled generically as “Penguin Eggs – Dr. Dick”. The ornithologist Alfred Newton recognized their true identity, a sensational find at the time. RCS promptly sold most of them. Three went to collector Robert Champley in exchange for anatomical specimens in 1864 (eggs #24–26) later finding their way to various museums. Four were auctioned at Stevens’s in 1865 (those became eggs #17–20). The remaining three stayed at RCS until after WWII, when they were sold in 1946 to Capt. Hewitt (#11–13). Thus, Newton’s RCS discovery ultimately seeded the collections of at least five museums and several private collectors.

Geographical Distribution

In the late 19th century, Great Auk eggs were concentrated in private British collections, but over time they have become widely distributed in institutional collections. Today the United Kingdom holds the largest share. At least 25–30 eggs are in UK museums (London NHM, Cambridge, Oxford, Norwich, Liverpool, etc.). Continental Europe also holds many egg. France (Paris) retains a few very old ones (#49–51); the Netherlands (Leiden, Amsterdam eggs #62–63), Germany (Oldenburg, Düsseldorf, Berlin, etc., eggs #60–61, #65), Italy (Florence #55), Portugal (Lisbon #64), Russia (St. Petersburg #68), Belgium (#66), and Switzerland (Geneva #67) each have one or two. In North America, the United States hosts perhaps 6–7 eggs (Harvard has the Thayer set of 6 eggs), and Canada has 2 (Toronto, Montreal). The Southern Hemisphere curiously ended up with one egg: New Zealand’s Te Papa holds egg #35, thanks to T.H. Potts carrying it to the antipodes.

Authenticity and Preservation

Fortunately, almost all of the eggs in the Tomkinson catalog are confirmed genuine. There have been instances of replicas or misidentified eggs. For example, the Zoological State Museum in Munich discovered that what they thought was a Great Auk egg was actually a skillfully painted replica, signed by a taxidermist around 1900. That egg had been counted in older lists but was removed once the forgery came to light in 2013. Such cases are rare. Making a convincing fake of the complex marbling is extremely difficult although all of the Great Auk eggs pictured in this article are in fact replicas created by the US based author and artist, Michael Naghan.

As noted, a few eggs were casualties of war although most eggs survived the turmoil of the 20th century. The Dresden egg #59 likely perished in WWII bombings or aftermath, and Lisbon’s egg #64 was very nearly lost in a 1978 museum fire. Museums now take extreme care. Eggs are often kept in secure, padded containers in climate-controlled storage, and only occasionally displayed to the public. As the Liverpool curator noted about the Earl of Derby’s egg, “it never leaves the box and no one is allowed to get too close”, which even influenced how it was photographed. It is shown peeking out of its protective box. This level of precaution is warranted given the eggs’ fragility, being hollow blown shells, and their irreplaceable nature.

Cultural and Scientific Significance

Each surviving Great Auk egg is not only a relic of an extinct species but also a touchstone in the history of science and conservation. They were among the first natural history objects to spur international laws. Iceland tried to protect the last auks in the early 19th century, albeit too late, and inspire the public’s realization of human-caused extinction. Many eggs have legendary associations. Some were erroneously blamed as “the last egg” taken from Eldey Island. For example, an egg Ketill Ketilsson allegedly smashed in 1844, though that may be apocryphal, and no identifiable shell remains. The mythos of the “last Great Auk egg” endures in literature and even at auctions. For instance, an egg from Canon Tristram’s collection was romantically touted in a modern book as “the last egg of the Great Auk”, though in truth it was just one of the last collected. From a scientific perspective, these eggs have recently found new purpose beyond display. Researchers have extracted DNA from inner membranes and old egg content traces to study the genetics of the Great Auk and even of its eggshell microbiome. Studies on eggshell thickness and shape have compared Great Auk eggs to those of their closest relatives, razor-bills and murres, to infer incubation behaviors. Because the eggs are so rare, such research is done with great care and often only on fragments or via non-destructive imaging.

Conclusion

The roughly 75 surviving Great Auk eggs have been painstakingly tracked and safeguarded over the past two centuries. This catalog documents each known specimen and its journey from wild nesting ledges on North Atlantic islets, into the cabinets of Victorian collectors, and finally into the conservation stewardship of modern museums worldwide. Together with the 78 or so stuffed skins and the skeletal remains of the species, these eggs constitute our last tangible links to the Great Auk. They continue to be studied for insights into the bird’s biology and to serve as poignant reminders of a species lost and of the importance of protecting those still with us.

Contact the author to commission the creation of any Great Auk replica.

References

Birkhead, Tim R., David L. Clugston, and Errol Fuller. 2023. “The Dispersal of Vivian Vaughan Davies Hewitt’s Collection of Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis) Eggs.” Archives of Natural History 50 (1): 191–206.

Clugston, David, and Errol Fuller. 2021. “Captain Vivian Hewitt and the Fate of His Collection of Birds’ Eggs and Specimens.” Biological Systems 2 (3): 349–57.

Fuller, Errol. 1999. The Great Auk. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

Grieve, Symington. 1885. The Great Auk, or Garefowl (Alca impennis, Linn.): Its History, Archaeology, and Remains. London: Thomas C. Jack. (Appendix includes list of 77 skins and 68 eggs known in 1885.)

Jourdain, F. C. R. 1935. “The Skins and Eggs of the Great Auk.” British Birds 28 (8): 233–234.

Parkin, Thomas. 1911. The Great Auk: A Record of Sales of Birds and Eggs by Public Auction in Great Britain, 1806–1910. Hastings, UK: Burfield & Pennells.

Tomkinson, P. M. L., and J. W. Tomkinson. 1966. “Eggs of the Great Auk.” Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History) 3 (July): 97–128.

Unsöld, Markus. 2014. “Two and a Half Auks – The History of the Great Auks, Pinguinus impennis, at the ZSM.” Spixiana 37 (1): 153–159.

Williams, G. C. 2013. “After Life: A Photographic Perspective on Endangered Species.” The Guardian, November 20, 2013.Yarrell, William. 1843. A History of British Birds, Vol. III. London: John Van Voorst. (Includes early account of Great Auk rarity and reference to an egg obtained in Paris for 5 francs.)