Reconstructing The Elusive Dodo Egg: Evidence and Insights

In the heart of Mauritius’s dry coastal forests, two dodo birds tend to a solitary egg nestled among fallen leaves and scattered twigs. Surrounded by towering tree buttresses and dappled light, the scene offers a an intimate glimpse into the nesting behavior and natural habitat of this iconic extinct species.

The egg of the dodo (Raphus cucullatus) remains one of the most enigmatic and least documented aspects of this extinct bird’s biology. With no confirmed eggshell fragments found on Mauritius and only a single contested museum specimen in existence, researchers have turned to historical accounts, comparisons with the closely related Rodrigues solitaire, and modern pigeon species to infer the likely size, appearance, and nesting behavior of the dodo. This article compiles available evidence from historical texts, museum records, and scientific studies to reconstruct the most accurate portrait possible of the dodo’s egg and its role in the bird’s life history.

Historical Descriptions of Dodo Eggs

Early records of the Dodo (Raphus cucullatus) make only brief mention of its egg. To this day, direct historical evidence remains scarce. No confirmed eyewitness sketch or painting of a dodo egg or nest is known from the age of discovery. The few written accounts emphasize the dodo’s tameness and the ease of hunting them, rather than their breeding.

In 1651, the French traveler François Cauche described a large flightless bird on Mauritius, which he called the “Oiseaux de Nazaret”, that “only lay one egg which is white, the size of a halfpenny roll”, in a nest of grasses on the forest floor. Cauche noted that the birds placed a smooth white stone about the size of a hen’s egg next to the single egg in the nest. This peculiar detail, which could be an observation or a sailors’ tale, suggests the dodo laid a lone, conspicuous egg on a simple ground nest.

Later, in 1693, François Leguat described a close relative of the Dodo, the Rodrigues solitaire laying one white egg in a nest of palm leaves on the ground. Both male and female solitaires fiercely guarded their nest territory, taking turns incubating the single egg. By analogy, the dodo may well have shared this one-egg clutch habit and attentive parental care. No known 17th-century writer described speckles or pigmentation, so the dodo’s egg was probably plain white or cream-colored, similar to many pigeon eggs.

Leguat wrote that solitaires built large ground nests about 40 cm high out of foliage and took an estimated seven weeks (49 days) to hatch their egg. Modern analysis suggests this incubation period was probably shorter (around 37 days) based on egg size models. Nevertheless, the consistent theme is that dodos and their kin invested in a single, well-guarded egg, reflecting a slow reproductive strategy in an island environment with few natural threats.

Size, Form, and Appearance of the Egg

Because so little direct evidence survived, scientists have pieced together the probable size and form of a dodo’s egg from comparative data and one alleged specimen. Cauche’s 1651 comparison, “the size of a halfpenny roll”, is vague to modern readers, but it has been interpreted by later researchers. Notably, Cauche used the exact same comparison for the egg of a great white pelican (Pelecanus onocrotalus). A pelican egg of that species weighs around 180 g and measures on the order of 9–10 cm long. This suggests the dodo’s egg was roughly similar in bulk to a swan’s or pelican’s egg, considerably larger than a domestic goose egg but much smaller than an ostrich egg. In modern terms, a dodo egg is often estimated at around 11-13 cm in length and perhaps 9–10 cm in diameter, though no intact wild egg has been measured. The mass is inferred to be around 150–180 g, consistent with an egg that would require about five to six weeks of incubation.

The shape of the dodo’s egg is thought to have been broadly oval but somewhat blunt at the ends. A 1953 description by museum curator Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer (see next section) noted that the egg was “far more blunt than any ostrich egg” she had examined, and resembled “the shape of a pigeon’s egg,” only much larger. In other words, the dodo egg likely had an elliptical form with both ends rounded, lacking a sharply pointed tip. This is consistent with many ground-laid bird eggs which often have oval or nearly spherical profiles for efficient incubation. Pigeon and dove eggs in general are broad elliptical with blunt ends, and the dodo being essentially a giant pigeon fits that pattern.

Shell texture and coloration can only be conjectured from limited evidence. The one presumed dodo egg (discussed below) is described as light cream in color with a matte, non-glossy finish. Its surface is somewhat grainy or chalky, not shiny, suggesting a thick, pitted eggshell similar to those of ratites or ground-nesting birds. Historical sources consistently mention white eggs, so the natural color was likely a plain off-white or cream without bold markings. This makes sense for an egg laid in a predator-free habitat, there being no need for camouflaging spots or blotches. Many pigeons lay pure white eggs, and the dodo appears to have been no exception. The shell was probably fairly thick to support a large bird incubating on it, and to withstand occasional rain or the weight of nesting material. No direct measurement of shell thickness exists, but by analogy a thick, durable shell would be expected. For example, crowned pigeons’ eggs have quite robust shells. Overall, the dodo’s egg can be visualized as a large, cream-white oval egg with a slightly rough, matte surface, about the size of a very big goose or small ostrich egg but shaped more like an oversized pigeon egg.

Reconstruction of Dodo egg

Museum Specimen and Reconstructions

Remarkably, only one physical egg has ever been purported to belong to a dodo. This egg is held at the East London Museum in South Africa, and its story traces back to the 19th century. According to museum records, the egg was brought from Mauritius in 1847 by a ship’s captain and given to a Miss Lavinia Bean, an avid egg collector. It remained in her family for generations. In 1935, her great-niece and famed discoverer of the coelacanth, Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer, inherited the egg and later donated it on loan to the museum. Courtenay-Latimer was convinced it was a genuine dodo egg and published a detailed letter in 1953 describing it and its provenance. She noted the egg’s large size and light creamy-white coloration, and argued that no other known bird on Mauritius could have laid such an egg after the dodo’s extinction. At the time, no references to any other dodo eggs existed in literature making this specimen truly unique.

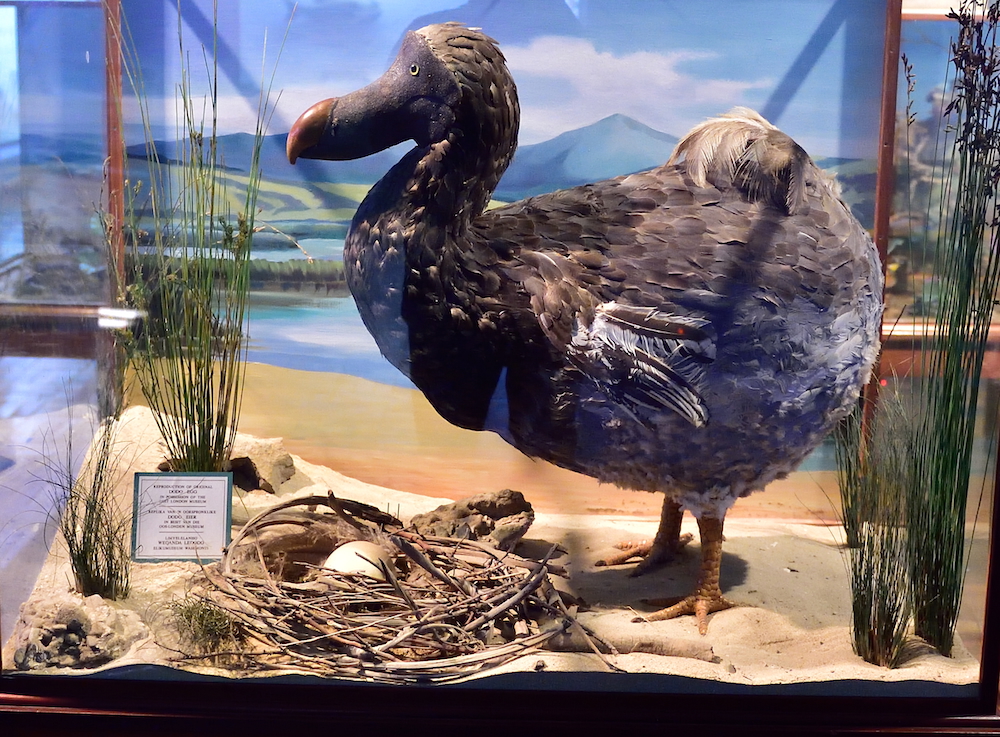

A cast of the alleged dodo egg displayed in a reconstructed ground nest at the East London Museum. The original eggshell is kept in storage for safekeeping.

Today, the East London Museum displays a replica (cast) of the dodo egg in a nest diorama, alongside a model of a dodo bird. The original eggshell is fragile and is kept locked in a strong-room for protection. The egg is ovoid and measures roughly 14 cm by 11 cm (as estimated from the cast), with a volume and shape consistent with the historical “half-penny roll” description. The shell’s surface is dull and porous, lacking any pigmentation. In the museum reconstruction, the egg lies on a shallow heap of dried grass and leaves, mimicking how dodos likely nested on the ground. This display gives the public a tangible sense of the egg’s scale. It appears about the size of a grapefruit or a small melon, much larger than a chicken egg.

It should be noted that the authenticity of the East London egg has been questioned by some researchers. Without DNA testing or definite provenance, a few have speculated that the egg might belong to another species, such as an ostrich or a large waterfowl, rather than a dodo. An ostrich egg, however, is much larger and more elongated than the exhibited specimen, and the historical chain of custody strongly ties the egg to Mauritius and the era shortly after the dodo’s extinction. In 2010, museum officials considered conducting genetic analyses on shell fragments to confirm the egg’s species, but an ownership dispute with Courtenay-Latimer’s heirs delayed such tests. As of 2025, the egg cast remains on display and in custody of the museum under a family loan agreement. No other museum or collection in the world has a claimed dodo egg, so this specimen, whether truly from a dodo or not, stands alone. Julian Hume, a leading dodo paleontologist, lamented that years of excavations in Mauritius have yielded no dodo eggshell fragments, highlighting how rare or quickly destroyed these eggs were in the fossil record.

Nesting and Incubation Behavior

Given the dodo’s island habitat and evolutionary lineage, scientists surmise that its breeding strategy was one of low output but high investment. The dodo likely laid just one egg per clutch, and probably only one clutch per year. This is an example of a K-selected reproductive strategy, producing few offspring, each requiring extensive parental care, as opposed to many offspring with minimal care. Support for this comes from the dodo’s large body size and the fact that tropical, fruit-eating birds often have slower growth and lower reproductive rates. A single, large egg would have demanded substantial resources to produce and incubate, suggesting the hen dodo laid infrequently, perhaps once annually, during a particular season. A recent study of dodo bone histology and climate patterns proposed that dodos bred at the end of the austral winter, when food was plentiful after fattening up in cooler months. Chicks would then hatch in early spring and grow rapidly during Mauritius’s mild spring and early summer, reaching a robust juvenile size by the cyclone season in January–March. This timing would ensure that by the time severe weather or food scarcity hit, the young dodos were strong and nearly adult-sized. After rearing a chick, the adults molted and renewed their feathers from March through July, then the cycle would repeat annually.

In the nest, it is very likely that both dodo parents participated in incubation and chick-rearing, as is typical for pigeons and doves. In modern pigeons, males and females take turns incubating, with one often sitting by day, the other at night. As a member of the pigeon family (Columbidae), the dodo almost certainly shared this unique trait; the parents would feed the newly hatched chick with “pigeon milk,” a curd-like secretion from their crops. This adaptation is seen in all pigeons and was probably crucial for a large chick that needed a rich diet before it could handle solid fruits and seeds. Notably, most pigeons lay two eggs, but the largest living pigeons such as New Guinea’s crowned pigeons lay only a single egg and devote all parental nutrition to that one squab. Researchers have hypothesized that larger pigeons are constrained to one-egg clutches because the demands of feeding young with crop milk limit the number of chicks the parents can sustain. The dodo, being larger than any modern pigeon, fits this pattern. One chick at a time would be all the parents could successfully raise.

The nest was almost certainly on the ground, as the dodo was flightless and built for life on terra firma. Dodos likely chose secluded spots under shrubs or between tree buttresses in the dry coastal woods of Mauritius. They would scrape together leaf litter, dry grass, or palm fronds into a rudimentary nest. Leguat’s account of solitaire nests describes a heap of palm leaves and grass, suggesting dodos did something similar with available vegetation. The chosen nesting areas might have been somewhat hidden but not inaccessible, since early sailors and settlers reported finding dodo nests and eggs easily. In fact, the vulnerability of these ground nests became tragically clear once humans and introduced animals arrived. Pigs, macaque monkeys, rats, and feral cats spread on Mauritius in the 17th century and would eagerly consume eggs or defenseless chicks. Mother dodos, with only a beak and stout body to defend the nest, had little chance against a rooting pig or a troop of rats. This predation pressure on the single egg and young was a major factor in the dodo’s rapid decline. By around 1640, dodos had become rare, likely because years of failed breeding due to eggs eaten by invasive mammals led to population collapse. In contrast, a smaller native bird like the red rail, a flightless rail on Mauritius, probably laid multiple eggs and hid its nest in dense marsh grass. It may have fared slightly better against predators. Unfortunately, the dodo’s life history, perfectly suited for an undisturbed island, proved disastrous once that island’s ecology was upended.

Despite these challenges, we can imagine some aspects of dodo parental behavior from their pigeon heritage. The parents likely were very attentive and protective of their nest. Like solitaires, they may have maintained a territory around the nesting site, chasing away other dodos to ensure plenty of food for their chick. If disturbed by a human or predator, a brooding dodo might have puffed up, hissed or snapped with its powerful beak, or even feigned injury to lure the threat away from the nest. Such behaviors are speculative but seen in many ground-nesting birds. Once the single chick hatched, blind and helpless, it would be fed crop milk for the first week or more, then gradually weaned onto softened fruits. The growth rate was probably rapid. A 2017 study of bone growth indicates dodo chicks reached near adult size in just a few months. This makes sense as a strategy to survive seasonal adversity: grow quickly when food is abundant. The young dodo might have stayed with its parents for some time even after fledging (dodos were precocial in walking ability but would still need guidance in foraging). Leguat observed solitaire parents accompanying their juvenile and even arranging “marriages”, grouping young birds together, once they were old enough. Dodos possibly had similar social rearing, where grown chicks roamed near the parents until the next breeding season approached.

Comparisons with Related Species

Because direct data on dodo eggs are so limited, scientists compare the dodo with its closest relatives to infer missing details. The dodo’s family, Raphinae, includes only the dodo and the Rodrigues solitaire which are both extinct. However, they are essentially giant ground pigeons, and their next kin are modern pigeon species. The Nicobar pigeon (Caloenas nicobarica), for example, is the dodo’s closest living relative. Nicobar pigeons nest on small islands and lay one elliptical white egg per clutch. Both parents incubate for about 30 days, and typically they raise one chick at a time. This offers a living model for how a primitive dodo might have reproduced in an island setting. Similarly, the crowned pigeons of New Guinea (Goura species), which approach a turkey in size, though still smaller than a dodo, always lay a single large white egg, about the size of a chicken’s egg, which hatches after ~28–30 days. Crowned pigeons feed their lone chick with crop milk and are devoted parents. The dodo, even larger, presumably also laid one egg and had a comparable or slightly longer incubation period. Approximately 35–37 days have been estimated for dodo eggs, aligning with its greater mass. These parallels reinforce the idea that the dodo’s reproductive biology was a scaled-up version of what we see in large pigeons today. That is, long incubation, intensive chick feeding, and strong bi-parental care.

The Rodrigues solitaire (Pezophaps solitaria) provides the best historical analogy. Leguat’s writings from 1691–93 describe how solitaires built their nests and how the male and female took turns incubating the one egg and zealously guarded their nesting area. He even noted that a solitaire would not tolerate another of its kind within 200 yards of its nest during breeding, indicating pronounced territoriality. This mirrors the presumed behavior of dodos, which likely also spread out in the woods, each breeding pair staking a patch of forest for their nest and food supply. Solitaires were observed to have gizzard stones and a diet of fruits and seeds. Leguat mentions finding a gray stone in a killed chick’s stomach. Likewise the dodo ingested gastroliths and fed on fallen fruits. All these similarities suggest that the dodo’s nesting habits, egg characteristics, and chick-rearing were not unique, but followed the general patterns of its pigeon lineage, adapted to an insular giant’s life.

Summary

The egg of the dodo was a sizable, pale, matte egg of singular importance, literally one per breeding attempt, incubated on the ground by devoted parent birds in the safety of Mauritius’s pre-human paradise. Its estimated dimensions (roughly 11–13 cm long), blunt pigeon-like form, white-cream color, and stout shell are consistent with what we know of other large pigeons and the scant historical descriptions. Artistic reconstructions and museum displays, informed by this knowledge, depict the dodo brooding a lone egg on a grass nest, a sight that must have been common in the Mauritius forests before 1600. Unfortunately, direct evidence is as ephemeral as the bird itself. No confirmed egg remains have been found in Mauritius’s subfossil deposits. Instead, the legacy of the dodo’s egg survives in secondhand reports and analogies. The dodo’s story underscores the vulnerability of island species with low reproductive rates. Its egg, once a symbol of new life, became one of the first casualties in humanity’s global impact on nature. The careful study and curation of the dodo’s egg, be it through scientific analysis or faithful museum replicas, help keep alive the knowledge of this lost species’ biology for future generations.

References

Bean, Lavinia. 1847. Personal Collection of Avian Eggs. Unpublished family archive, later donated to East London Museum, South Africa.

Courtenay-Latimer, Marjorie. 1953. “Letter Regarding the Dodo Egg Specimen.” East London Museum Archive Correspondence. East London Museum, South Africa.

Cauche, François. 1651. Relations Veritables et Curieuses de l’Ile de Madagascar. Paris: Pierre Lamy.

Fuller, Errol. 2002. Dodo: From Extinction to Icon. London: HarperCollins.

Fuller, Errol. 2016. Extinct Birds. Rev. ed. Ithaca, NY: Comstock Publishing Associates.

Gibbs, David, Eustace Barnes, and John Cox. 2001. Pigeons and Doves: A Guide to the Pigeons and Doves of the World. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Hume, Julian P. 2006. “Reappraisal of the Dodo (Raphus cucullatus) and Its Extinction.” Historical Biology 18 (2): 65–89.

Hume, Julian P. 2011. Systematics, Morphology, and Ecology of Extinct Island Doves. British Ornithologists’ Union Occasional Publication.

Hume, Julian P., and Michael Walters. 2012. Extinct Birds. London: T. & A.D. Poyser.

Hume, Julian P. 2023. Dodo: The Bird Behind the Legend. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Jackson, Christine E. 1999. A Newsworthy Naturalist: The Life of William Yarrell. London: The Ray Society.

Leguat, François. 1708. Voyages et Aventures de François Leguat et de ses Compagnons en Deux Iles Desertes des Indes Orientales. Amsterdam: Jean Louis de Lorme.

Livezey, Bradley C. 1993. “An Ecomorphological Review of the Dodo and Solitaire.” Journal of Zoology 230 (2): 247–292.

Pereira, Sérgio L., and Allan J. Baker. 2006. “A Mitogenomic Timescale for Birds.” Molecular Biology and Evolution 23 (1): 1731–1740.

Rex, John. 2005. “The Mystery of the Dodo Egg.” Museums Journal of Southern Africa 28 (1): 42–48.

Stattersfield, Alison J., Michael J. Crosby, Adrian J. Long, and David C. Wege. 1998. Endemic Bird Areas of the World: Priorities for Biodiversity Conservation. Cambridge, UK: BirdLife International.

Turvey, Samuel T., and Julian P. Hume. 2021. “Human-Induced Extinctions in Island Ecosystems.” Biological Conservation 255: 108974.