Reconstructing Bird Egg Pigmentation: A Scientific and Artistic Guide

Birds’ eggs exhibit a surprisingly narrow palette of natural pigments, yet they produce a stunning variety of colors and patterns. In fact, nearly all the hues seen on bird eggshells come from just two pigments: a bluish-green one (biliverdin) and a reddish-brown one (protoporphyrin). These pigments, laid over the white calcium carbonate eggshell, can mix and layer to create everything from the famous teal of a robin’s egg to the speckles on a quail egg. For artists seeking to recreate these colors with high fidelity, understanding the science behind egg pigments and finding their closest paint equivalents is key. Below is a detailed guide to the pigments of bird eggs and the artist-grade colors that best match them, complete with examples and mixing tips.

Scientific Background: Two Pigments, Endless Egg Colors

Birds essentially use a two-color paint set to color their eggs. Research in the 1970s confirmed that blue-green biliverdin and rusty-brown protoporphyrin are responsible for almost the entire gamut of eggshell colors and patterns. These are both tetrapyrrolic compounds derived from heme (the blood pigment). Biliverdin is a bile pigment (a breakdown product of hemoglobin) that imparts blue to green hues, while protoporphyrin IX is a heme precursor that gives red-brown tones. In a sense, nature’s “limited palette” for eggs consists of one cool color and one warm color, applied in varying concentrations on the shell’s white carbonate base.

Each eggshell’s color is determined by the presence and ratio of these pigments. A pure biliverdin coating yields a blue or teal egg, pure protoporphyrin yields a brown or reddish egg, and combinations produce intermediate colors like olives and purples. The pigments can be distributed uniformly or in patterns. Biliverdin typically permeates the shell layers to produce a solid blue/green shell, whereas protoporphyrin is often deposited last in the shell gland, creating surface spots or a bloom of color. Notably, eggshell coloration is a superficial layer – the inside of a colored egg is usually blue in biliverdin-rich eggs and white in protoporphyrin-only eggs, since the blue-green pigment permeates the shell thickness whereas brown pigment stays on the exterior.

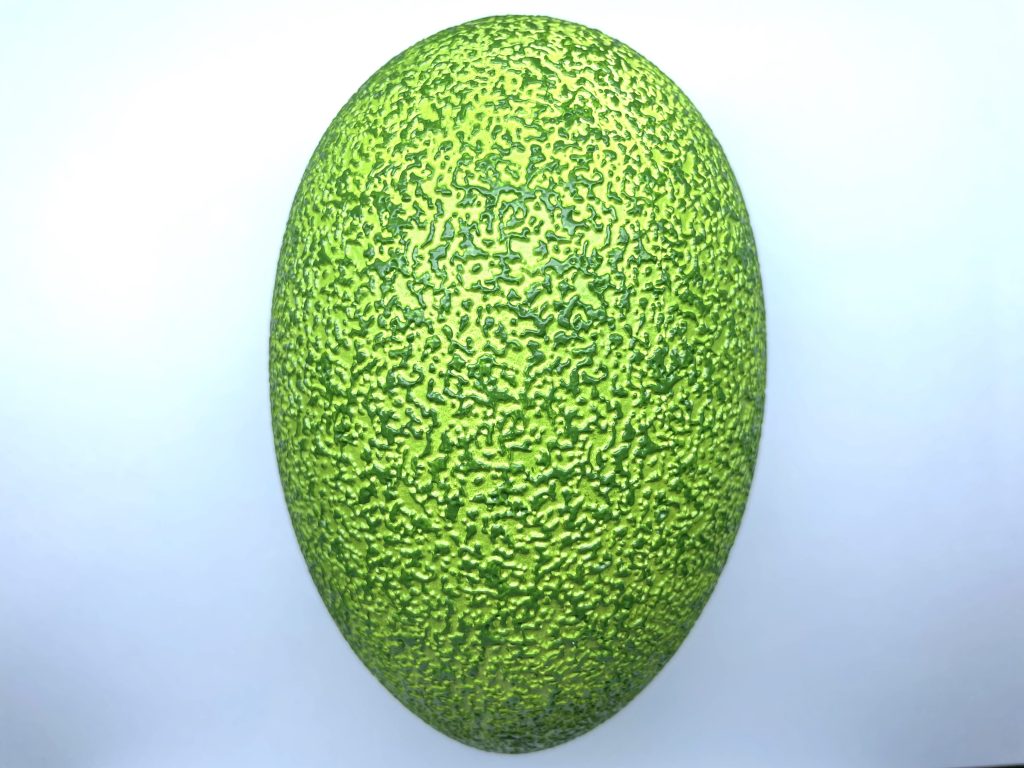

For over a century, biliverdin and protoporphyrin were thought to be the only eggshell pigments. Recent studies, however, have identified a couple of rare exceptions. The vividly colored eggs of certain tinamou species (South American ground birds) contain two additional pigments: yellow–brown bilirubin and red–orange uroerythrin, found alongside biliverdin in those shells. These novel pigments (also heme-derived) create extraordinary shell colors like “guacamole green” and purplish-brown in tinamous. Such findings expand the egg color palette slightly, but for nearly all other bird species, blue-green biliverdin and red-brown protoporphyrin remain the core pigments driving eggshell coloration.

With the science in mind, we can translate these natural pigments into the language of art. Below, we examine biliverdin and protoporphyrin in detail, their visual qualities and examples in nature, and identify the artist pigments and paint colors that best emulate their hues. We’ll also discuss how to mix these colors to mimic the blended tones seen on many bird eggs.

Biliverdin: The Blue-Green Egg Pigment

Biliverdin is the blue-green pigment responsible for the striking colors of many birds’ eggs. Chemically, it is a tetrapyrrole (biliverdin IXα) produced by the breakdown of hemoglobin in the mother’s bloodstream, then deposited into the eggshell during formation. In the shell, biliverdin can create colors ranging from aqua blue to turquoise to soft green, depending on its concentration and whether it binds with metals. For example, in some eggs it forms a zinc chelate that can influence the hue. This pigment is famously behind the “robin’s egg blue” color. A brilliant teal-blue that has even become a standard color name in art and design.

Example eggs: Birds that lay blue or green eggs are showcasing biliverdin. The American Robin’s eggs are a classic example. A bright sky-blue turquoise with no markings, colored uniformly by biliverdin. Many other thrushes, like the song thrush, lay biliverdin-tinted blue eggs sometimes with brown speckles from added protoporphyrin. Mallard ducks also lay eggs colored by biliverdin but in their case it is heavily desaturated by the white calcium carbonate shell. The Southern Cassowary lays a huge green egg so rich in biliverdin that bumps on the shell look almost teal-black. In all these cases, biliverdin yields a blue-green hue that can be quite vivid. Higher biliverdin concentration produces deeper, more saturated blues, whereas lower concentration or mixing with the eggshell’s calcium carbonate gives paler bluish pastels. Some eggs appear more greenish if a yellowish component is present or if a bit of brown pigment mixes in, but pure biliverdin generally leans toward a cyan/teal tone.

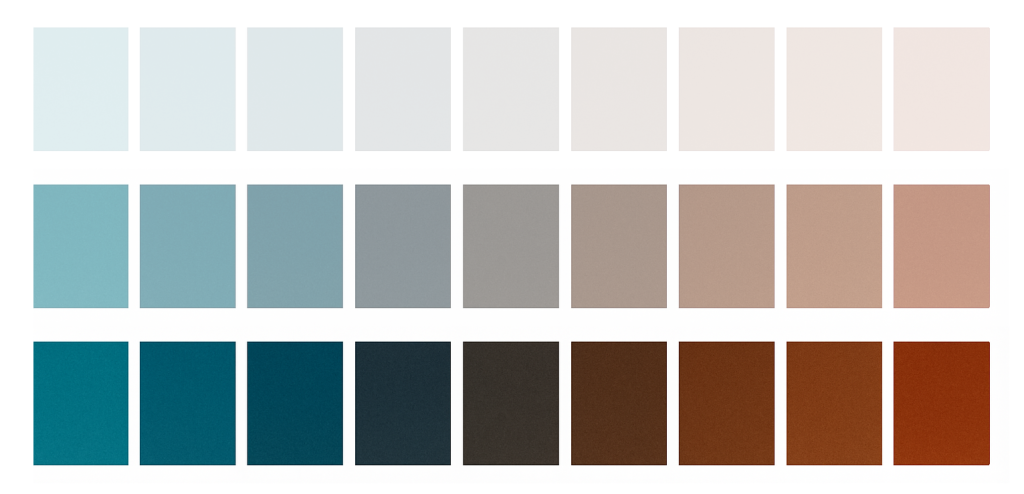

Artistic Equivalent – How to Replicate Biliverdin’s Blue-Green: To recreate the brilliant blue-green of biliverdin on canvas or paper, artists should reach for strong cyan/teal pigments. One of the best matches is Phthalocyanine Blue (Green Shade), commonly known as Phthalo Blue. This modern synthetic pigment (often labeled PB15:3 in acrylics, oils, and watercolors) has a very intense cyan-blue color with a slight green bias, very much in the same family as robin’s egg blue. Phthalo Blue (Green Shade) straight from the tube is deeper and more saturated than most bird eggs, but by lightening it with white and/or warming it slightly with a touch of yellow, you can closely mimic the eggshell tint. In practice, mixing a tiny amount of a yellow pigment (e.g. cadmium or ochre) into Phthalo Blue and then adding white yields a convincing robin’s egg blue. The yellow nudges the blue towards turquoise, and the white brings it to the pastel opacity of an eggshell. This combination mirrors the way biliverdin’s blue-green appears somewhat soft and milky on an eggshell rather than as a dark jewel tone.

Beyond Phthalo Blue, there are other options: Cobalt Teal Blue (PG50) is an inorganic single-pigment paint that comes almost exactly in a robin’s-egg teal shade out of the tube. It was historically costly but is prized for that greenish sky-blue color that is an excellent match for many biliverdin-colored eggs. Cerulean Blue (PB35/36), a gently greenish light blue, can also approximate a pale egg blue when diluted with white, though it is typically a bit duller. Viridian Green (PG18), a traditional translucent green, can be used in mixtures to push a blue towards a turquoise. For instance, Viridian + a little Cerulean + white can create a soft duck-egg green. However, Viridian itself might be a touch too green. Many bird eggs are more on the blue side of teal. For most purposes, Phthalo Blue + White with a possible tweak of a tiny dab of warm yellow or even a touch of Phthalo Green will give the bright blue-green one associates with biliverdin, whether it’s the pure blue of a robin’s egg or the slightly greener aqua of a starling’s or duck’s egg.

When painting a subject like a clutch of bluebird or robin eggs, remember that biliverdin has a gentle vibrancy. The color is vivid but naturally softened by the chalky eggshell. You’ll often achieve the most lifelike result by tinting a high-chroma blue-green with some white. Titanium White for opacity, or Zinc White for transparency to get that soft, matte eggshell look. Also consider the lighting. Real eggs may have subtle shading and texture. You might mix a hint of complementary color, such as a tiny bit of burnt sienna or another brown, into the shadow areas of a blue egg to tone it down, since real eggshells aren’t uniformly neon-blue. But as a base hue, a teal-leaning blue is your biliverdin analog in the artist’s palette.

Protoporphyrin: The Red-Brown Egg Pigment

Protoporphyrin IX is the reddish-brown pigment that gives many bird eggs their browns, rusts, and speckles. Chemically, it’s a porphyrin, related to the heme molecule but without the iron. Birds deposit this pigment onto the outer layer of the eggshell, especially in the last hours before the egg is laid. This pigment produces earthy colors ranging from deep chocolate brown to brick red to pale tan or pinkish, depending on concentration and distribution. Protoporphyrin is often responsible for mottled patterns because it tends to be laid on in the shell gland as the egg rotates. It can form spots, speckles, or a blush of color on the otherwise white or blue shell surface. In effect, nature uses protoporphyrin as a brown “ink” or wash over the eggshell canvas.

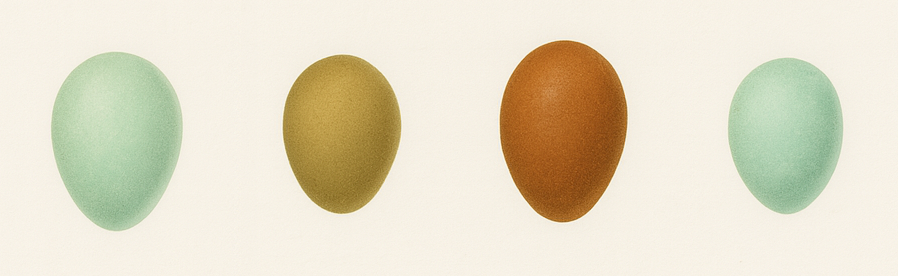

Examples eggs: Any bird egg that is brown, beige, reddish, or speckled with those colors is colored by protoporphyrin. A spectacular example is the vivid red-brown shell of the Cetti’s Warbler egg. The color is created by protoporphyrin deposited over a white shell. Remove the brown pigment, via a mild acid wash, and the shell underneath is white, showing that protoporphyrin is essentially a surface coating. Many songbirds’ eggs are white or blue with brown speckles. For instance, the Ring Ouzel eggs are blue with small red-brown spots. Those spots are protoporphyrin applied late in the laying process. Raptors like Peregrine Falcons lay eggs that are almost entirely brick-red/brown with darker freckles. In these, protoporphyrin is so concentrated that the egg appears a rich terracotta or mahogany color. Another example is the California Quail egg, which is often a pale buff heavily spattered with dark brown splotches. Again, protoporphyrin pigment applied in uneven blotches gives that camouflaged look. Ground-nesting birds such as plovers and nightjars commonly have eggs with complex speckling and scrawls in brown tones for camouflage. All of that is variations of protoporphyrin. At high concentration protoporphyrin can look reddish-brown. At low concentrations, a yellowish-tan to a faint tint over white. In some cases it even appears nearly purple-brown when very dark with layered spots being almost black. But chemically it’s the same pigment.

Insert four egg images – Cetti’s Warbler, Ring Ouzel, Peregrine Falcon, California Quail

Artistic Equivalent – How to Replicate Protoporphyrin’s Browns: The warm, rusty browns of bird eggshells can be matched with the earth pigments on an artist’s palette. The classic choice is Burnt Sienna, an iron-oxide earth pigment (PBr7) known for its transparent reddish-brown hue. A wash of Burnt Sienna in watercolor looks very much like the stain of color on a chicken egg or the light speckles on a songbird egg. It has the advantage of being transparent enough to simulate how real egg pigment lets the shell texture show, yet rich enough in masstone to achieve darker spots.

Another useful pigment is Burnt Umber. This is a darker brown earth, also PBr7 but calcined from raw umber. Burnt Umber is less red and more neutral brown. It can be used for the deepest dark speckles or shadows on eggs. For example, the very dark almost-black spots on a quail egg could be rendered by mixing Burnt Umber with a bit of Ultramarine Blue to cool and darken it or by using a deep brown like Sepia. However, if one prefers a single-pigment solution, Perylene Maroon or Van Dyke Brown in watercolor can give nearly black-brown spots too. Generally, though, Burnt Sienna + Burnt Umber will cover the range of most egg browns.

For eggs that have a brighter red-brown (like a peregrine falcon’s brick-colored egg), you might introduce a pinch of red into the Burnt Sienna. Historically, Indian Red (PR101, a red iron oxide) is a very opaque brick-red that could match a falcon egg’s color, but its opacity might be a drawback if you want a translucent look. An alternative is a modern transparent organic pigment like Transparent Red Oxide or Quinacridone Burnt Orange, which have high chroma and transparency. Still, Burnt Sienna remains the go-to for most applications. It nicely captures that “dried-blood” brown and can be lightened or darkened easily.

Replicating Complex Egg Colors

While some bird eggs are pure blue or pure brown, many have mixed hues. For instance, olive greens, turquoise with brown freckles, or creamy pink with rusty splotches. In nature, these arise from combinations of biliverdin and protoporphyrin in varying proportions. For an artist, this is directly analogous to mixing our blue-green and red-brown paints. By understanding this interplay, we can recreate those nuanced egg colors with high fidelity.

- Olive and Sage Greens: An olive-green egg is essentially a blue egg with an overlay of brown. Chickens known as “olive eggers” and various species of Curlew for example, have a genetic blue shell that is then coated with brown pigment.

The Phthalo Blue + Burnt Sienna combination is artistically powerful. It can yield teal, olive, or brown depending on proportions. This mirrors how nature’s two pigments form a continuum of egg colors. Phthalo blue and burnt sienna together can produce everything from brown-red to teal to olive green and almost black greens just by varying the mix. So with these two paints on the palette, you effectively have the same “two-pigment system” birds use.

- Pale and Pastel Eggs: Some birds lay off-white, cream, or pinkish eggs such as some pigeons, doves, or owls. These are usually cases of very low protoporphyrin on a white shell, sometimes with a hint of biliverdin. To replicate a cream or pink egg, mix mostly white with just a tiny dab of color. A touch of Burnt Sienna gives a warm creamy or salmon pink tone like the blush on some eggs when freshly laid. A speck of Light Red Oxide or Venetian Red in white can also simulate that pink cast. For a pale greenish egg such as the barely perceptible green of some owl eggs, add a minute amount of your blue-green into white. Essentially, treat it like a white with a tint. These subtle colors require restraint in mixing; it’s often less than 5% colored pigment to 95% white to get the effect.

- Bluish vs. Greenish Variations: Among blue eggs, some lean more sky-blue and others more aqua. For a greener egg that looks seafoam or aqua green, incorporate a bit more yellow. For a pure blue with less green, like some robin eggs that appear true blue, mix in a tad of a more neutral blue like Ultramarine or a hint of red to slightly purple the Phthalo. Remember that real biliverdin often has a slight green tint, but lighting can make an egg look bluer.

- Purple or Gray Eggs: Although rare, some bird eggs, like those of certain tinamous mentioned earlier, can have a purplish cast. That usually comes from mixing blue-green + a lot of brown which can yield a gray or mauve. To mimic a subtle purplish-brown egg, you might mix Phthalo Blue + Burnt Sienna + a touch of a magenta or dioxazine purple to push it into a wine-brown hue. Generally, adding a red-violet to the mix of our two core pigments can simulate those rare tints. Since uroerythrin, the rare pigment in tinamous, is a bright red-orange, one could approximate that by adding an orange or red to our base brown.

Conclusion

When striving for high fidelity in depicting bird egg coloration, it pays to think like a pigment chemist and an artist. Knowing that biliverdin = blue-green and protoporphyrin = red-brown is the foundation. From there, select artist-grade pigments that embody those colors. Phthalo Blue (Green Shade) and Burnt Sienna are a powerful pair that correspond closely to the egg pigments’ hues in intensity and temperature. For slightly different effects, supplement them with neighbors like Cobalt Teal, Viridian, or Burnt Umber as needed to nail specific shades and values.

Sources:

- M. Hauber, Audubon Magazine – Cracking the Code on Egg Coloration (2015)

- UConn Dept. of Chemistry – Bird Eggshells Just Became More Colorful (2020)

- C. Brückner et al., Scientific Reports 10:11264 (2020) – Eggshell pigment study

- L. Helton, American Poultry Assoc. – Blue Eggshell Pigments (2021)

- Wikipedia – Robin egg blue (color entry); Wikimedia Commons (images of robin eggs and chicken eggs)

- D. Doreau (artist) – on mixing Phthalo Blue & Burnt Sienna for versatile greens (analogous to egg pigment mixing).