The Elephant Bird’s Giant Egg: Legend, Legacy, and Latest Discoveries

In the winter of 1992, a nine-year-old boy in Western Australia astonished his classmates by bringing an enormous fossil egg to school for show-and-tell. The giant egg, bigger than a football, had been found half-buried in the dunes of Cervantes Beach during a family outing. The giant find was smooth, weathered ivory in color, and large enough that the child needed both arms to cradle it. Only later did museum scientists realize this was no dinosaur egg, but the egg of the legendary elephant bird of Madagascar, an animal long vanished from the Earth. For nature enthusiasts and scientists alike, the discovery was a tangible link to a lost world of giant birds, inspiring wonder and curiosity. What was the creature that laid such a colossal egg? How did it live, and why did it disappear? The story of the elephant bird’s egg weaves together biology and paleontology, myth and history, and cutting-edge science. It is a tale that spans continents and centuries, from ancient Indian Ocean legends of giant birds, to modern museum displays and DNA laboratories. Here is the tale of an egg as big as a basketball, holding secrets of the past.

A Giant Bird and Its Giant Egg

Elephant birds are not one species but an extinct family of species known as Aepyornithidae, These enormous flightless birds that once roamed on the island of Madagascar and comprised three separate groups or genera; Mullerornis, Vorombe and Aepyornis. They are the largest birds that ever lived as far as we know. These flightless birds towered over 3 meters or 10 feet tall and weighed up to 500–700 kg. A recently described species named Vorombe titan may have been even heavier, possibly up to 860 kg. Imagine an ostrich, but far more robust, with tree-trunk legs and a heavy torso, wandering through Madagascar’s forests and plains. Despite their ostrich-like build, elephant birds were actually most closely related to the diminutive kiwi of New Zealand, a surprising twist revealed by DNA studies. In fact, their brains and senses also echoed this kinship. An analysis of skulls shows elephant birds probably had very small optic lobes which is the main center of visual processing, much like kiwi. This suggests they were nocturnal or twilight-active creatures that relied more on smell than sight. One can picture these giants moving quietly through dark Malagasy woodlands at night, using their keen sense of smell to seek out fruits or foliage.

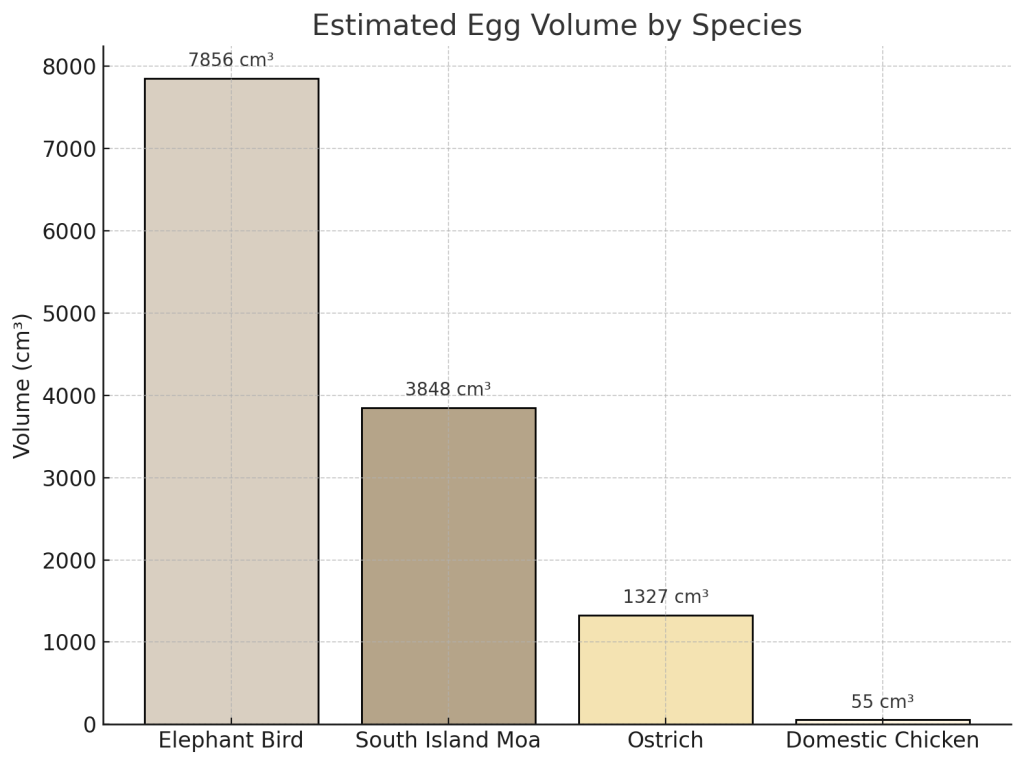

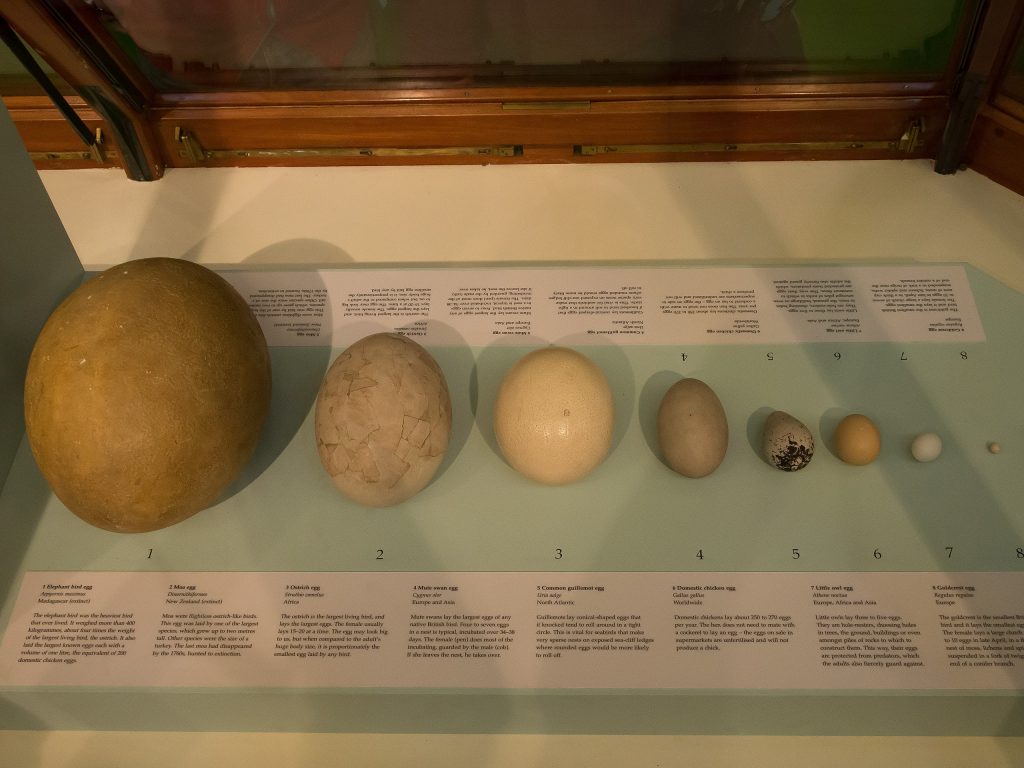

Just as impressive as the bird itself were its eggs. Elephant bird eggs are the largest eggs known to science thus far. A typical egg measured up to 33–34 cm long and 24 cm in diameter, roughly the size of a volleyball. The egg’s volume was about 7 to 8 liters (about 2 gallons) in the biggest specimens, which is greater than any dinosaur egg yet discovered although some dinosaur eggs are much longer but considerably thinner. In weight, the eggs are about 10 kg (22 pounds). To put it in perspective, one elephant bird egg had the same volume as about 120–150 chicken eggs. Even an ostrich egg, the largest egg of any living bird today, looks petite next to an elephant bird’s. You would need 6–7 ostrich eggs to equal the volume of one egg. The eggshells were extraordinarily thick and strong being up to 3–4 mm thick in the big species, more than three times thicker than an emu eggshell. These hardy eggs could withstand considerable weight and damage. In one striking example, an intact subfossil elephant bird egg was found after likely floating across the ocean for thousands of kilometers. Two such eggs were discovered on Australian beaches, having drifted on ocean currents all the way from Madagascar.

From fossil evidence, scientists can sketch some aspects of the elephant bird’s nesting and reproduction. Elephant bird eggshell fragments are abundant in certain areas of Madagascar, especially in the south and southwest coastal regions. Entire beaches near places like Faux Cap are said to be littered with bits of eggshell that are the remnants of ancient nesting grounds where generation after generation of elephant birds laid their colossal eggs in the sand. Unlike the carefully tended nests of smaller birds, the elephant bird likely nested in simple scrapes or pits on the ground, similar to ostriches or other ratites, perhaps relying on sun-warmed sand to help incubate the massive eggs. A clutch probably consisted of only one or two enormous eggs at a time. Producing such a gigantic egg is a huge investment of energy and calcium, so these birds were not prolific layers. In fact, analysis of female bone tissue suggests they had special calcium reservoirs to draw on for eggshell production, as modern birds do. The developing chicks inside were also correspondingly large and well-formed. Remarkably, paleontologists have even found an embryonic skeleton preserved inside an elephant bird egg, with the chick dying 80–90% of the way through its incubation. It showed that elephant bird hatchlings were strong-limbed and likely precocial, ready to walk soon after hatching just like ostrich or megapode chicks. One can imagine a palm-sized elephant bird chick pecking its way out of a shell thick as china, emerging as a sturdy, downy creature already capable of following its mother through the underbrush.

In life, elephant birds were gentle, giant herbivores that browsed on plants and fruits. Isotopic analyses of eggshell carbon have revealed nuances in their diet. For example, a 2022 study found that some elephant bird species (like Aepyornis hildebrandti) grazed on grassy foods nearly half the time, while others browsed on higher vegetation. Their habitat preferences may have varied. Larger species such as A. maximus likely roamed dense forest as their larger olfactory bulbs hint they sniffed out fruit in woodlands, whereas smaller species lived in open scrub or plains. With no natural predators aside from perhaps crocodiles or large carnivorous mammals, these huge birds could afford a slow life history. They grew slowly and likely reproduced gradually, living for many decades and laying a few enormous eggs in a lifetime. For thousands of years, elephant birds thrived as kings of their island. That is until a new apex predator, humans, arrived on Madagascar’s shores.

Myths, Legends, and Early Encounters

Long before scientists knew of Aepyornis, the peoples of the Indian Ocean told stories of giant birds that could snatch elephants and carry off unwary sailors. The Malagasy people themselves had a name for the elephant bird, vorompatra, meaning “bird of the Ampatra” (Ampatres being a region in the south of Madagascar) or by some accounts “bird of the open spaces”. To the Malagasy, the vorompatra was likely known through the huge eggs and footprints these birds left behind, even if sightings of the reclusive creatures were rare. It’s easy to imagine how awe-inspiring it would be to stumble upon an egg larger than one’s head while roaming the Malagasy bush. Such finds could give rise to legends of colossal, almost supernatural avians.

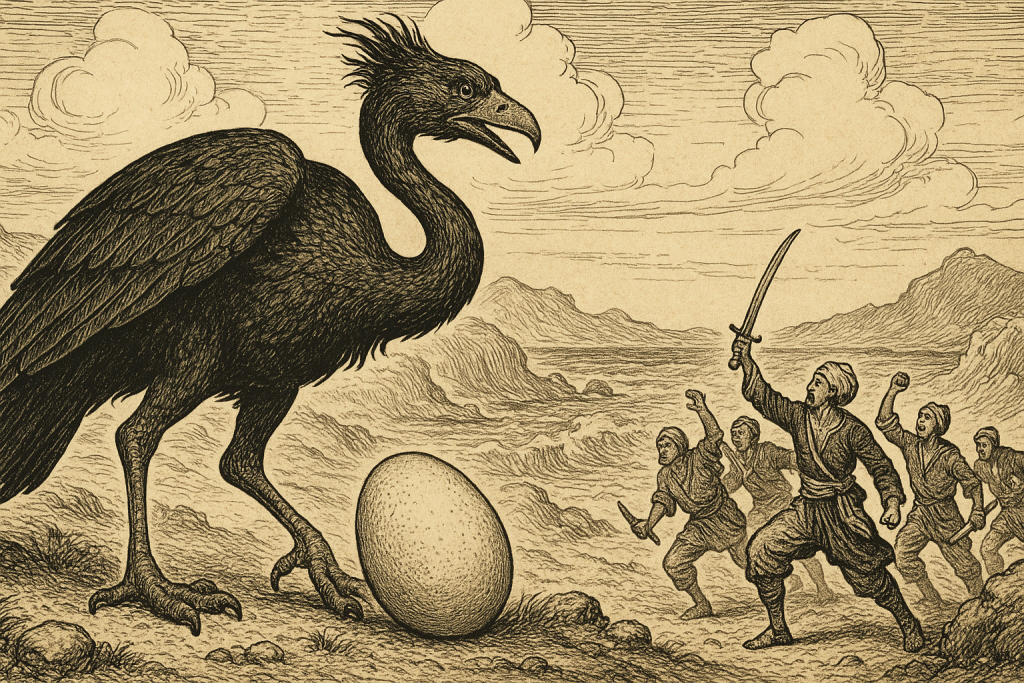

Beyond Madagascar, the wider world first learned of these giant birds through travelers’ tales that blended fact and fantasy. As early as the 9th century, Arabian and Persian sailors spoke of a monstrous bird called the roc (or rukh) in their seafaring lore. These stories found their way into The Arabian Nights, where Sinbad the Sailor encounters a roc’s colossal egg only to incur the wrath of the parent bird. The roc was said to carry off elephants and whales in its talons, feeding them to its young. Such hyperbole was surely fiction, yet it resonated with kernels of truth. Marco Polo, the Venetian explorer, recorded in his 1298 travelogue that on Madagascar there lived a great bird called “rukh” which “appeared like an eagle but of enormous size”. Polo wrote that the locals described this bird as strong enough to “seize an elephant with its talons”. Clearly an exaggeration, since no elephants live in Madagascar, but one that gave the “elephant bird” its popular name in later retellings. Likewise, the great Moroccan traveler Ibn Battuta in the 14th century mentioned hearing of gigantic birds during his sojourns near the western Indian Ocean. These early accounts, though fantastical, hinted at an underlying reality. Something very large was out there in Madagascar, sparking the imaginations of those who heard of it.

For the indigenous Malagasy, the giant vorompatra may have been more than just an animal. It could have featured in oral traditions or as a cautionary figure. “Don’t wander too far, or the great bird might get you”. We have fewer written records of Malagasy myths from those times, but later generations certainly regarded the elephant bird with a mix of fear and reverence. Even after the creatures became scarce, their eggshells were used by local people. Fragments of elephant bird eggs have been found fashioned into bowls or ornaments, suggesting that the shells, which can hold several liters of liquid, served as handy containers for water or food. To this day, stories persist in Madagascar of enormous eggs being discovered by farmers or children, underscoring how the species lives on in folk memory.

The final flicker of the elephant bird in historical record comes from a French colonial account. In 1658, Étienne de Flacourt, the French governor of Madagascar, wrote of a great bird he called “vouron patra”, describing it as a large, ostrich-like bird inhabiting the remote southern marshes. Flacourt noted that the bird laid eggs like an ostrich and was said to be uncatchable by the locals. It’s unclear whether Flacourt ever saw one himself or was reporting secondhand stories, but his mention is often cited as the last probable sighting (or last anecdote) of living elephant birds. If indeed some elephant birds survived into the mid-17th century, they were likely very few, living in isolated pockets. Most scientific evidence, however, suggests they disappeared earlier, probably around 1000 CE. Nevertheless, Flacourt’s account shows the legend persisted a while longer. After that, the giant of Madagascar slipped into obscurity, remembered only in Malagasy lore and traveler’s myths, until modern science re-discovered it.

Fossils and Eggs in the Modern Era

The reappearance of the elephant bird in human knowledge came in the 19th century with the era of exploration and natural history collection. In the 1840s and 1850s, French naturalists working in Madagascar started finding huge bones and eggshell fragments in the coastal sands. In 1851 the species Aepyornis maximus was formally described by zoologist Isidore Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire. Imagine the astonishment in European scientific circles when reports came of bird bones heavier than an ostrich’s and eggs larger than any existing animal could produce. These subfossil remains, not yet turned to stone, but dried and preserved in the ground, proved that the “mythical” roc had been a very real creature.

Perhaps the most dramatic finds were the intact elephant bird eggs that occasionally turned up. One such discovery occurred in 1864, when travelers in Madagascar unearthed a complete gigantic egg. The British author W. Winwood Reade wrote excitedly that “the existence of the Roc of Marco Polo and The Arabian Nights is now proved by the discovery of an immense egg in Madagascar”. Although Reade was mistaken about the roc (the egg was of Aepyornis, not a fantasy bird), his reaction captures the Victorian-era fascination with these eggs. Museums and collectors scrambled to acquire them. The Paris Museum of Natural History received many of the bones, and other museums in London, New York, and elsewhere sought the eggs. An elephant bird egg, after all, is an unforgettable display item. It dwarfs every other bird egg. Curators found that even if they had only broken fragments, they could piece them together like a giant 3-D puzzle to reconstruct a full egg. Many of the eggs in museums today are actually composites assembled from multiple shells found at old nesting sites. Sir David Attenborough famously obtained a pile of elephant bird eggshell fragments during a filming trip to Madagascar in the 1960s. Years later, he painstakingly fitted them together into a complete egg, a personal treasure he featured in his documentary Attenborough and the Giant Egg.

By the early 20th century, scientists had a pretty clear picture of the elephant bird from skeletal remains. They confirmed it was a giant, flightless ratite and pondered how it lived and why it went extinct. What caused the elephant bird’s demise? Here, the eggs themselves provide an important clue. Archaeologists have found subfossil eggshells at human habitation sites in Madagascar, some with burn marks and charring, indicating they were cooked over fires. Others have cuts or holes that suggest humans deliberately opened the eggs to eat the contents. Considering that each elephant bird egg contained the nutritional equivalent of dozens of chicken eggs, it would have been a highly attractive food source for early Malagasy people. Why risk hunting a 500-kg bird when you could steal an egg from a nest and carry it off? One estimate holds that a single elephant bird egg could make an omelet to feed an entire village. Aside from egg-gathering, there is also evidence in the form of cut marks on bones that humans occasionally hunted the birds themselves, or at least scavenged their remains. The timing of the elephant bird’s extinction correlates with the expansion of Madagascar’s human population and the burning of forests for agriculture around 800–1200 CE. By around a millennium ago, habitat loss and overharvesting likely sealed the fate of these gentle giants.

A Record-Breaking Egg in Comparison

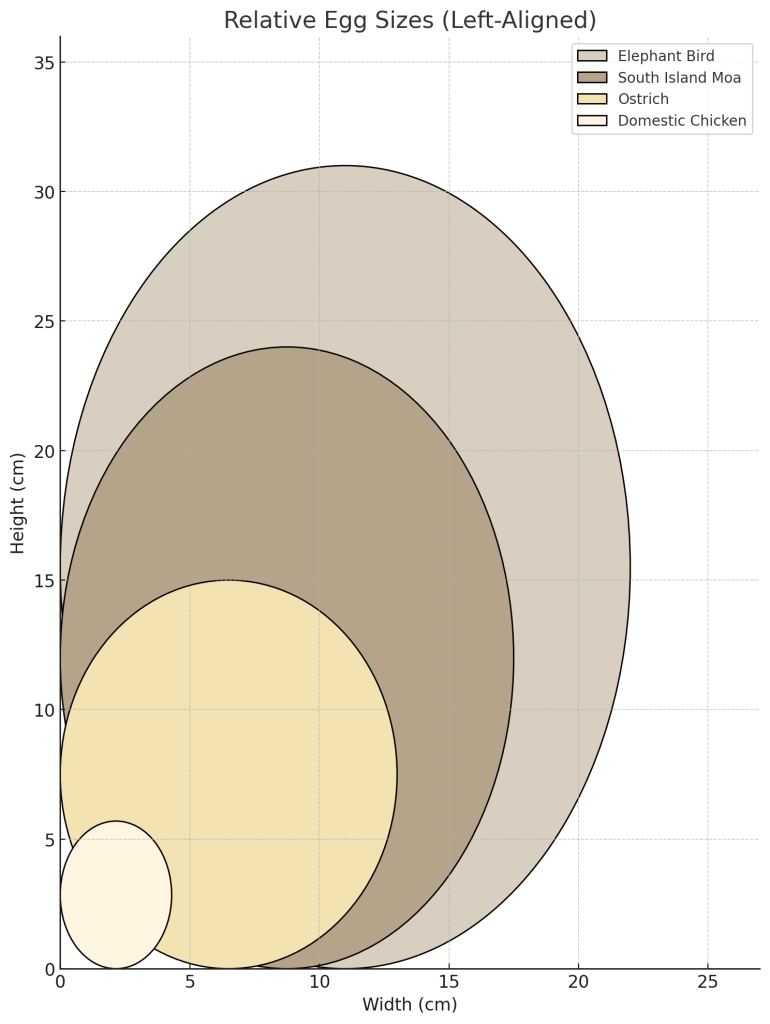

The elephant bird egg holds the record as the largest egg of any animal, and comparing it to other giant eggs highlights just how exceptional it is. If you lined up an ostrich egg next to an elephant bird egg, the ostrich egg would look like a little sibling, perhaps only one-fifth the mass of the elephant birds. Another extinct giant, New Zealand’s moa, also laid impressively large eggs. The South Island giant moa (Dinornis) stood over 3.5 meters tall, larger than an elephant bird in height, though more slender in build. Moa eggs reached about 24 cm in length. In volume and weight, the biggest moa eggs were roughly 2–3 liters. This is huge by normal standards, but still only perhaps one-third the volume of the largest Aepyornis eggs. Interestingly, moas had a peculiar reproductive twist. The largest moa species had relatively undersized eggshell thickness for the egg’s volume, suggesting the shells were somewhat fragile. It’s hypothesized moa eggs might have been incubated in moss or by males with minimal movement to avoid breakage. The elephant bird, by contrast, evolved a much thicker shell, possibly an adaptation to harsher, hotter conditions or to deter scavengers from breaking in.

And what of dinosaur eggs? Despite the towering size of many dinosaurs, their eggs were generally smaller than one might expect. The largest known dinosaur eggs from giant sauropods or oviraptorosaurs are usually elongated ovals about 30–40 cm long, but with volumes less than 5 liters. No dinosaur egg discovered so far rivals the elephant bird’s in volume. This is partly because extremely large dinosaurs tended to lay multiple smaller eggs rather than one enormous one. The elephant bird, being constrained by how much a single baby bird could develop inside an egg, seems to have pushed that limit to the maximum. If we imagine a scale of all egg-layers, from tiny hummingbird jellybean sized eggs to titanosaurs and elephant birds, the elephant bird sits at the extreme end of the spectrum.

The structure of the elephant bird egg also aided its preservation. That ultra-thick shell, rich in calcium carbonate, is highly durable. Elephant bird eggshell fragments can survive for centuries or millennia in sandy soil without disintegrating. In contrast, thinner eggs like most dinosaur eggs are often crushed flat or leached away unless rapidly buried and mineralized. The robust nature of Aepyornis eggshell means scientists today have an abundance of pieces to study, and even intact eggs are not unheard of. It’s estimated that fewer than 20 complete elephant bird eggs exist in collections worldwide, making them extremely rare museum treasures. In 2013, an intact elephant bird egg offered at a Christie’s auction was expected to fetch over $45,000, a testament to their uniqueness. Most of those that survive are either on display in natural history museums or held in national collections where they continue to spark public imagination about Madagascar’s lost giants.

The Egg in Modern Science and Culture

Today, elephant bird eggs occupy an interesting place at the intersection of science, education, and even art. Walk into a natural history museum’s fossil hall or prehistoric life exhibit, and you might encounter one of these giant eggs exhibited alongside dinosaur skeletons and Ice Age mammals. Museums often use the elephant bird egg as a tangible symbol of the wonder of the natural world – something seemingly unbelievable yet real. For example, the London Natural History Museum proudly displayed an elephant bird egg in a line-up of bird eggs to show visitors the astonishing range of egg sizes. The American Museum of Natural History in New York included Aepyornis in its “Mythic Creatures” exhibition, connecting the scientific specimen to the legends of the roc that it inspired. Seeing the egg in person, people often remark that it looks like “something from a dragon’s nest” – it can truly dwarf a human head. In the Canterbury Museum in New Zealand, one such egg sits in storage (a composite assembled from half an egg and scattered fragments), reminding us that New Zealand’s own giants, the moa, had relatives even grander across the ocean.

Beyond museum halls, elephant bird eggs have made appearances in popular culture and media. As mentioned, Sir David Attenborough’s fascination led to a charming documentary where this renowned naturalist handles a reconstructed egg with childlike glee, tracing the story behind it. The egg also features in H.G. Wells’ short story “Aepyornis Island,” a fictional tale about a sailor who hatches an elephant bird from a retrieved egg, with comedic and tragic results. These cultural references highlight a deeper point: the elephant bird egg serves as a storytelling catalyst. Through it, we connect to a bygone epoch when gigantic birds roamed, and we reflect on human roles in nature – as discoverers, as storytellers, and, regrettably, as agents of extinction.

Scientifically, these eggs have become precious data capsules. In recent years, researchers have discovered that even in the absence of bones, eggshells can yield DNA and chemical clues about the extinct bird. The dense mineral matrix of the shell protects ancient molecules. In fact, eggshell DNA was long thought impossible to extract, but advances proved otherwise. A pioneering study in 2018 recovered fragments of ancient DNA from elephant bird eggshells, definitively confirming the elephant bird-kiwi evolutionary link that had shocked biologists. Building on that, in 2023 a team led by Alicia Grealy conducted the first comprehensive DNA analysis of elephant bird eggshells from across Madagascar. They sampled nearly a thousand eggshell pieces, some up to ~6,000 years old, and sequenced their mitochondrial genomes. The results revealed that the elephant birds in the southern part of the island turned out to be less genetically diverse than expected implying perhaps only two main groups or genera were present there in the Holocene. Intriguingly, one eggshell from far northern Madagascar belonged to a completely different lineage indicating a “mystery” elephant bird that had not been captured in the skeletal fossil record. This suggests that these birds had a wider distribution and more complex evolution than we knew, even splitting into distinct regional forms separated by mountains or habitats.

Moreover, the chemistry locked in an eggshell can inform us about the bird’s environment. Isotopic analysis of oxygen and carbon in elephant bird eggshells has been used to reconstruct past climates and diets. If an eggshell shows certain oxygen isotope ratios, it can indicate the aridity of the landscape when the female laid the egg since drinking water isotopes get recorded in the shell carbonate. Carbon isotopes tell us what types of plants the mother was eating. As noted earlier, one study found differences in diet between species: some grazed more on C₄ grasses, whereas others browsed on C₃ shrubs and fruits. Such multidisciplinary research, combining paleontology, geochemistry, and genomics, underscores how the elephant bird’s egg continues to teach us about Madagascar’s ecological history.

Finally, the elephant bird egg has become emblematic in conservation discussions. While the species is long gone, Madagascar today faces ongoing biodiversity crises. Some conservationists and educators use the elephant bird as a cautionary example of how human overhunting, habitat destruction, and introduced diseases can wipe out even the most formidable of creatures. The image of humans plundering giant eggs for a meal resonates with modern concerns about unsustainable resource use. There have even been musings, purely theoretical for now, about whether de-extinction science could one day resurrect an elephant bird, perhaps by editing the genome of a close living relative (like a large cassowary or ostrich) and using an ostrich as a surrogate for an elephant bird egg. This remains the realm of science fiction at present, but it speaks to the enduring allure of these birds. The eggs that survived for a thousand years in a dune may yet have a hand in the future, if only by inspiring us to care for the giants that remain.

The Legacy of a Lost Giant

In the end, the elephant bird’s egg is more than a paleontological specimen. It’s a story capsule. Each eggshell fragment, each carefully preserved oval in a museum, connects us to the Pleistocene and Holocene forests of Madagascar where a female elephant bird carefully deposited her precious offspring-to-be. It connects us to the early Malagasy who perhaps cautiously approached a massive bird’s nest to gather a meal, and to the Arab sailors who spun yarns of the roc based on floating eggs or sailors’ exaggerations. It connects to adventurers and scientists, from Marco Polo to Étienne de Flacourt, from 19th-century naturalists to 21st-century geneticists. For nature enthusiasts, the elephant bird egg is a reminder of nature’s capacity for wonder and surprise. A reminder that once, not so long ago in geological time, a truly fantastical bird shared our world. As we marvel at the sheer size of the elephant bird’s egg, we are also invited to marvel at the intricate web of life and a story still unfolding from a shell long cold.

References

- Wogan, Hicks. “This monstrous mama laid the world’s largest egg.” National Geographic, February 4, 2025.

- Line, Brett. “Elephant Bird Egg Auction Inspires a Hunt.” National Geographic, April 1, 2013.

- Yong, Ed. “The Surprising Closest Relative of the Huge Elephant Birds.” National Geographic (Not Exactly Rocket Science), May 22, 2014.

- American Museum of Natural History. “Strike from the Sky” (Mythic Creatures exhibition text). New York: AMNH, 2007.

- Grealy, Alicia. “Extinct elephant birds were 3 metres tall and weighed 700kg. Now, DNA from fossil eggshells reveals how they lived.” The Conversation, Feb 28, 2023.

- Sade, Agard. “Elephant birds: First DNA study of fossil eggshells hints new lineage.” Interesting Engineering (summary of Nature Communications study), March 2023.

- MadaMagazine. “The life of elephant birds.” Mada Magazine (online), 2018.

- Canterbury Museum. “A Big Bird’s Egg.” Canterbury Museum Stories, 2021.

- Pauline Conolly. “An Elephant Bird Egg at ‘Show and Tell’.” PaulineConolly.com (blog), March 15, 2018.

- National Museum of Ireland – Natural History. “Elephant Bird Egg from Madagascar.” Museum.ie (exhibit description), n.d..

- Long, John A, Patricia Vickers-Rich, K Hirsh, E. Bray, and Claudio Tuniz. 1998. “The Cervantes Egg an Early Malagsy Tourist to Australia.” Records of the Western Australian Museum 19 (1): 39–46. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/part/260612.