Reconstructing the T-Rex Egg

Recent discovery of embryonic tyrannosaurid remains has shed light on the possible characteristics of Tyrannosaurus Rex eggs. These consist of a tiny jaw bone and claw from closely related tyrannosaurid species, Daspletosaurus and Albertosaurus. From these fossils, scientists inferred that tyrannosaur hatchlings were about 0.9 meters (3 feet) in length, implying they came from very large eggs with the developing T-Rex curled up inside. Researchers estimate T. rex eggs would have been roughly an enormous 43 cm long (~17 inches). In this article we will explore how reconstructing T. rex eggs can come from indirect evidence and comparisons to relatives, rather than direct fossil eggs.

Clues from related theropods

In the absence of T. rex egg fossils, paleontologists look to closely related theropods, especially other tyrannosaurids and large coelurosaurs, for clues. The recently discovered embryonic bones of an Albertosaurus and Daspletosaurus are suggests that tyrannosaurid eggs were large and elongated on the order of approximately 40cm in length. Paleontologists had found large elongate dinosaur eggs in Late Cretaceous rocks long before finding those embryos. These fossil eggs, assigned to the oogenus Macroelongatoolithus, measure 34–61 cm long and have an elongated form. They were initially attributed to giant theropods like the Asian tyrannosaur Tarbosaurus or even T. rex, but recent research revealed they actually belonged to enormous oviraptorosaurs that are giant relatives of Oviraptor. Nonetheless, these Macroelongatoolithus eggs provide a useful model. They show what huge theropod eggs look like and how they were arranged. Each egg is highly elongated (length-to-width ratio around 2–3) and often found in paired clusters within circular clutches. The paired arrangement indicates the mother had two functional oviducts laying eggs two at a time which is a trait generally seen in non-avian dinosaurs. Smaller coelurosaurs like oviraptorids (Citipati, Oviraptor and kin) also laid elongate eggs measuring 14–18 cm long laid in carefully arranged nests. They would deposit eggs in pairs around themselves in a ring, often sitting atop the clutch in a brooding posture. Taken together, these relatives suggest that T. rex’s eggs were elongated, paired, and laid in a nest (rather than live-born or randomly scattered), following the general theropod reproductive pattern. In short, although we lack T. rex eggs, its lineage and cousins indicate that its eggs would have been large, elongate, and handled in a manner similar to other egg-laying theropod dinosaurs.

Macroelongatoolithus eggs in the Naturhistorisches Museum Wien

Size and shape of the eggs

Size

Based on the tyrannosaur embryonic remains and comparisons to large theropod eggs, a T. rex egg is estimated at roughly 38–45 cm in length and perhaps about 12-18 cm in diameter at its widest. One analysis suggests tyrannosaur eggs were around 43 cm long. This size is in the same ballpark as the gigantic Macroelongatoolithus eggs from China (~40 cm long by 11–14 cm wide). By volume, such an egg would hold several liters, likely weighing on the order of 4–6 kg (for comparison, the largest bird egg, from the extinct elephant bird, weighed ~9–10 kg). These would rank among the largest eggs of any dinosaur although the largest known dinosaur eggs, the Asian Macroelongatoolithus at ~60 cm long, exceeded what we expect for T. rex. Tyrannosaur eggs were almost certainly elongated in shape rather than spherical. Dinosaur egg shapes range from round to very elongate, and most elongate examples come from theropods. It’s likely a T. rex egg was a long oval, perhaps somewhat asymmetrical with one end more tapered. Many non-avian theropod eggs have one blunt end and one pointed end, similar to bird eggs. This streamlined shape would have fit well within the mother’s pelvis and facilitated laying two at a time.

Shell thickness and structure

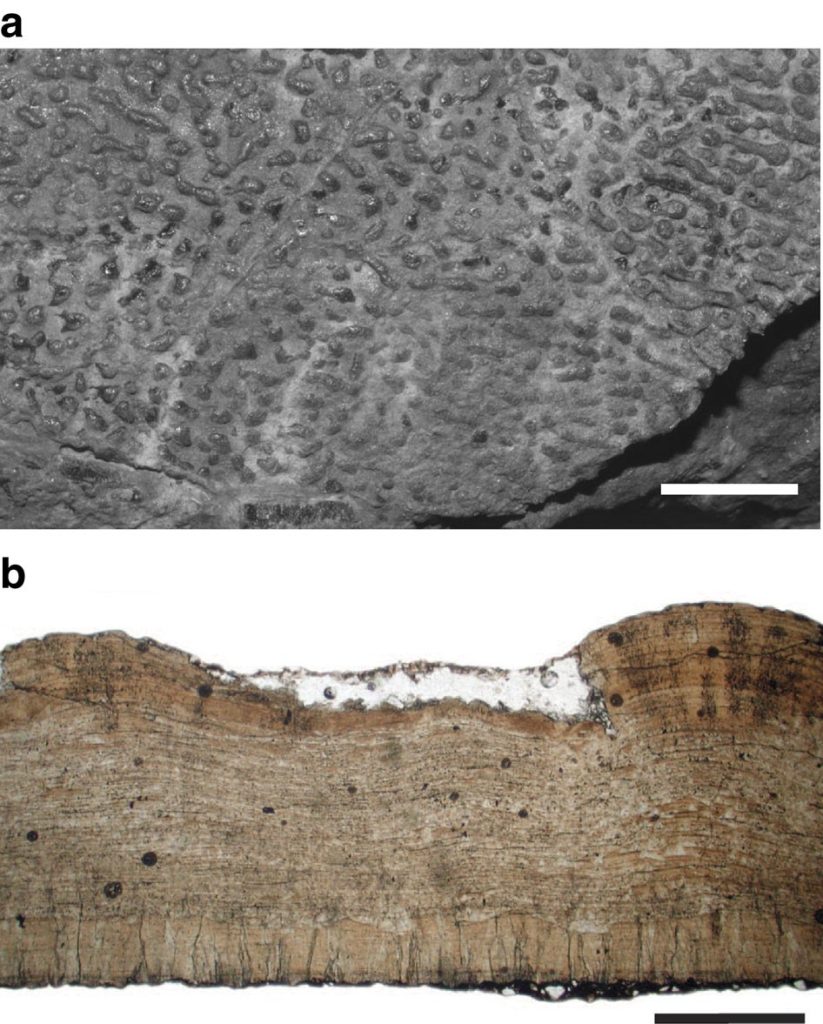

If T. rex eggs were hard-shelled like those of other known theropods, their eggshell was probably on the order of ~1.5 mm thick. Large elongate theropod eggs have shell thickness ranging from about 1.0 to 2.2 mm, so T. rex would be comparable. The shell was likely composed of the typical two-layered calcite structure seen in theropod eggs: an inner cone-layer (mammillary layer) and an outer columnar layer. This two-layer architecture is a diagnostic feature of theropod and bird eggs, distinct from the single-layer shells of most other dinosaurs. Some non-avian theropod eggs even have a third external crystalline layer like modern bird eggs, so T. rex eggshell may have had a similar complexity. In terms of porosity, tyrannosaur eggs would have had numerous microscopic pores for gas exchange, as all amniote eggs do. We don’t have a measured pore density for T. rex, but studies of analogous eggs show high overall gas conductance consistent with a thick but porous shell that allowed the developing embryo to breathe.

Surface texture

The outer surface of a T. rex eggshell was likely textured and/or ornamented rather than smooth. Unlike most modern bird eggs, many dinosaur eggs, especially from the Late Cretaceous, show rough, sculpted surfaces with nodes, bumps, and ridges. The giant elongate eggs assigned to Macroelongatoolithus have “noticeable nodes, rough spots, and ridges” on their outer shell. It’s reasonable to infer T. rex eggs had a similar rugged, matte texture. Such ornamentation may have helped strengthen the shell or allowed better moisture and gas flow when partially buried in nest materials. In summary, a T. rex egg was probably a big, elongated oval with a thick, bumpy shell, looking quite unlike a chicken’s egg and more similar to the eggs of other large non-avian theropods.

Eggshell surface (a) and microstructure (b) of Macroelongatoolithus eggs associated with Beibeilong

Egg coloration and pigmentation

What color were T. rex eggs? Scientists can draw insights from both dinosaur relatives and pigment chemistry studies. Research in the last decade has revealed that some non-avian dinosaurs laid colored eggs. Notably, eggshells from Late Cretaceous oviraptorosaurs have been found to contain the same pigments that color bird eggs: biliverdin (blue-green) and protoporphyrin IX (reddish-brown). A study in 2017 detected blue-green pigmentation in fossil eggs of an oviraptorid dinosaur (Heyuannia), indicating those eggs were a bluish-green hue in life. This discovery upended the old assumption that all dinosaur eggs were white, showing that bird-like egg colors originated in dinosaur predecessors. However, the evidence suggests that egg coloration evolved partway through dinosaur evolution, not universally in all species. A broad survey of fossil eggshell chemistry using Raman spectroscopy found that egg color only arose within a specific clade of theropods, the Eumaniraptora which includes birds, troodontids, and dromaeosaurs, as well as oviraptorosaurs. More primitive dinosaurs, including sauropods, ornithischians, and likely basal coelurosaurs like tyrannosaurids, show no trace of eggshell pigment. In other words, colorful eggs appear to have a single evolutionary origin in maniraptoran theropods, and groups outside that, like T. rex, probably continued the ancestral trend of non-pigmented eggs.

The idea of hard-shelled, plain, whitish, T-Rex eggs aligns with the idea that tyrannosaurs probably covered their eggs in nests, negating the need for camouflage coloration. Studies have correlated egg color with nesting style. Dinosaurs that laid eggs in open, exposed nests often had colored shells to camouflage or strengthen them, whereas those that buried or covered their eggs tended to have unpigmented, white shells. For example, oviraptorids built open nests and had blue-green eggs, presumably to blend with vegetation and perhaps provide UV protection for the egg. By contrast, buried eggs, like those of crocodiles or some duck-billed dinosaurs, are uncolored. Given that T. rex likely did not have fully exposed, bird-like nests (see below), there would be little evolutionary pressure for brightly colored eggs. Thus, a strong hypothesis is that T. rex eggs were a dull, unpigmented white. It’s worth noting this is an inference. If future evidence showed T. rex eggs were exposed, then by analogy they could have had pigment. But currently the weight of phylogenetic and nesting behavior evidence suggests no color. In summary, unlike the speckled blues and greens seen in some dinosaur eggs, a T. rex egg was probably plain white, similar to a crocodile’s egg, due to its more concealed incubation strategy.

Nesting strategy and clutch size

A fossilized ring-shaped clutch of large theropod eggs (Macroelongatoolithus, likely from a giant oviraptorosaur). The eggs (40–45 cm long) are arranged in a circular nest with a central open space. This pattern suggests the heavy parent could brood by sitting in the middle of the ring without crushing the eggs.

Link

How T. rex nested and incubated its eggs is an important question. Based on related dinosaurs, we can sketch a likely scenario. Tyrannosaurs probably dug a shallow nest pit or mound on the ground to lay their eggs. Unlike birds, which have a single ovary and lay eggs one by one, a female T. rex would have had two functional oviducts and laid eggs in pairs. She may have deposited a pair of eggs, rotated a bit, laid another pair, and so on, arranging them in a roughly circular clutch. For smaller theropods like Citipati, a complete clutch could consist of about 12–22 eggs laid in concentric circles. A T. rex, with much larger eggs, likely laid fewer eggs per clutch, perhaps 10–15 eggs in a single nesting attempt. The clutch might have been spread over an area several meters across. For example, the giant oviraptorosaur Beibeilong (which laid 0.45 m eggs) is thought to have built nests up to ~3 m in diameter. A full-sized T. rex, significantly heavier than Beibeilong, would need at least as much space for her eggs.

Nesting environment is key to understanding T. rex’s strategy. Many paleontologists suspect tyrannosaurs did not simply leave their eggs fully exposed on the surface. The high inferred porosity of large theropod eggs supports this idea: eggs like Macroelongatoolithus have a gas conductance 3–6 times higher than predicted for eggs of similar size in open-air nests. Such high porosity suggests the eggs were incubated in a humid, covered setting, either buried in soil/sand or covered by vegetation, similar to how modern crocodiles or megapode birds incubate eggs in mounds. It’s likely that T. rex eggs were at least partially buried or covered by the parent with nesting materials. The parent ( we don’t know which sex tended the nest) might have piled plant matter over the eggs to keep them warm and moist, relying on decay heat (like a compost pile) or sunlight on the mound, rather than body heat. This would align with the eggs’ probable white coloration (no need for camouflage under cover) and the shell adaptations for high gas exchange in a covered nest.

Could an animal as large as T. rex have brooded its eggs directly, like a bird? This is a matter of debate. Smaller theropods certainly brooded by sitting on their eggs. The famous “Big Mama” Citipati fossil shows an oviraptorid crouched over the nest, covering it with its arms. For gigantic dinosaurs, though, the risk of crushing eggs was real. The evidence from large oviraptorosaurs is intriguing. They developed a clever strategy of arranging eggs in a ring with a vacant center, creating a donut-shaped clutch. The largest species left a hole in the middle of the nest big enough for the parent to sit in without touching the eggs. This way, they could still impart warmth or protection while their weight was supported by the ground in the center of the ring. If T. rex practiced any form of brooding, a similar strategy would be necessary. It might have positioned itself near or among the eggs. For example, sitting in the middle of a circle of eggs or beside a cluster such that its bulk didn’t directly press on them. It’s also conceivable that tyrannosaur parents did not routinely sit on the eggs at all, but rather guarded the nest from nearby. Large crocodilians today do not incubate with body heat. They simply cover the eggs and stand guard. T. rex may have behaved more like a crocodile or a megapode bird, ensuring the nest temperature and humidity were stable (via covering/uncovering) and defending the nesting site from predators, rather than physically warming the eggs.

Oviraptor nest at the American Museum of Natural History

In terms of parental care, some scientists have proposed that hatchling tyrannosaurs, being fairly large and mobile, might have been quite precocial. Meaning they could leave the nest soon after hatching and perhaps follow the parents for protection or fend for themselves to some degree. A baby T. rex was the size of a turkey or medium sized dog at birth, which is enormous by animal standards, and it likely could walk shortly after hatching. This might reduce the need for lengthy brooding or feeding at the nest. Still, guarding and guidance by parents would greatly increase survival, and it’s hard to imagine T. rex as a completely neglectful parent given that crocodiles carefully watch over their nests and help hatchlings.

In summary, T. rex probably nested on the ground, laying a moderate number of very large eggs, which were partly or fully covered for incubation. The parents likely guarded the nest and possibly helped regulate its conditions, though whether they literally sat among the eggs to brood remains uncertain. The large egg size and fewer offspring suggest a reproductive strategy of investing heavily in each egg/offspring as opposed to laying dozens of tiny eggs and leaving. This would imply that nest protection and perhaps some level of care, at least until hatching, was important in tyrannosaurs, even if we don’t know the exact mechanics of how a 6–9 ton animal tended its brood.

Conclusion

An historical note underscores the uncertainty in this field. The case of the misidentified T. rex eggs. For years, large fossil eggs found in Mongolia and North America were tentatively labeled as belonging to tyrannosaurs, given their size. As more evidence came to light, those eggs were reclassified as being from giant oviraptorosaurs, not tyrannosaurids. This taught researchers to be cautious; assigning eggs to a particular dinosaur without an embryo is tricky. So, at present, no egg can be definitively called T. rex’s. Any future claim of a T. rex egg will require either an embryonic bone inside or extremely strong contextual evidence. Paleontologists continue to search badlands and rock formations for that elusive tyrannosaur nest or egg. If and when one is found, some of the above notions may be confirmed or overturned. Until then, our picture of Tyrannosaurus rex’s eggs, their size, shape, texture, color, and the way they were cared for, remains a scientifically reasoned estimate assembled from the best available evidence in related creatures. It is a compelling picture, but one that awaits direct validation from the fossil record.

Sources

Books

Carpenter, Kenneth, Karl F. Hirsch, and John R. Horner, eds. Dinosaur Eggs and Babies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

Chiappe, Luis M., and Lowell Dingus. Walking on Eggs: The Astonishing Discovery of Thousands of Dinosaur Eggs in the Badlands of Patagonia. New York: Scribner, 2001.

Carpenter, Kenneth. Eggs, Nests, and Baby Dinosaurs: A Look at Dinosaur Reproduction. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999.

Web

University of Alberta Folio news (2021) – Scientists unearth first baby tyrannosaur fossils ever found

Link

Funston et al. (2021), Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences – Dinosaur embryo find helps crack baby tyrannosaur mystery

Link

ScienceDaily (2021) – “Tyrannosaur embryos were size of a Border Collie”

Link

National Geographic (2020) – report on tyrannosaur embryos inferring 17-inch egg length

Link

Zelenitsky et al. (2017) Nature Communications – Beibeilong embryo in giant egg (giant oviraptorid eggs). May 11, 2017 | Everything Dinosaur Blog

Link

Simon (2014) – MSU Thesis on Macroelongatoolithus eggs (size, structure, porosity)

Link

Wikimedia Commons (Henan Museum) – image of Macroelongatoolithus clutch showing ring-shaped nest

Link

Wiemann et al. (2017/2018) – discovery of blue-green pigment in dinosaur eggs (Nature, reported by Sci. American)

Link

Tanaka et al. (2018) – study of oviraptorosaur nesting posture vs body size (Biology Letters, reported by ScienceNews)

Link

Carpenter (1999) – eggshell porosity and dinosaur nesting ecology

Link

General references on dinosaur reproduction: AMNH, Dinosaur Eggs and Babies exhibit materials

Link